- Home

- Kate Bolick

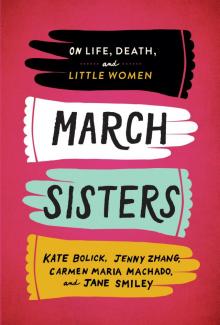

March Sisters

March Sisters Read online

MARCH SISTERS: ON LIFE, DEATH, AND LITTLE WOMEN

Volume compilation copyright © 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

“Meg’s Frock Shock,” by Kate Bolick.

Copyright © 2019 by Kate Bolick.

“Does Genius Burn, Jo?” by Jenny Zhang.

Copyright © 2019 by Jenny Zhang.

“A Dear and Nothing Else,” by Carmen Maria Machado.

Copyright © 2019 by Carmen Maria Machado.

“I Am Your ‘Prudent Amy’” by Jane Smiley.

Copyright © 2019 by Jane Smiley.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of America’s best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by America’s

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors, and our popular

Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 978–1–59853–629–4

Preface

Meg’s Frock Shock

Kate Bolick on Meg

Does Genius Burn, Jo?

Jenny Zhang on Jo

A Dear and Nothing Else

Carmen Maria Machado on Beth

I Am Your “Prudent Amy”

Jane Smiley on Amy

About the Authors

AS JANE SMILEY notes in the pages of this book, we tend to think and speak of Louisa May Alcott’s Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy as if they were real. Readers have had an intense interest in the stories of the four March sisters from the beginning. After the publication of part one of Little Women in 1868 (part two followed in 1869), Alcott was inundated with letters, many of them addressed to Jo, demanding to know what happened to the four sisters. “Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life,” Alcott wrote in her diary. “I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please any one.” Readers would continue to send fan letters to Alcott’s publisher until at least 1933, forty-five years after her death. In the decades after the novel’s release, “Little Women clubs” became common across the country, with members taking on the identities of the March sisters, just as Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy took on the identities of the Pickwick Society members in the novel. More recently, Little Women has served as inspiration to screenwriters, directors, and actors in more than a dozen film and television adaptations. Ursula K. Le Guin, Patti Smith, Susan Sontag, and J. K. Rowling, among numerous others, have claimed Little Women as an influence. Many more future novelists and feminists will be emboldened by Jo’s example, while others will continue to find encouragement in Meg’s egalitarian marriage, Beth’s self-sacrifice and love of family, and Amy’s relentless pursuit of art and beauty.

Often first encountered in early adolescence, Little Women is one of those childhood favorites readers return to in later years, for its pleasures are many and changeable, and its life lessons about love, loss, patience, duty, hard work, and of course marriage are always worth hearing (especially if one has forgotten them). Rereading Little Women in adulthood, we may appreciate complexities previously undetected, or we may, with the shock of recognition, come to understand something about our own childhood—and hence about ourselves. But Little Women remains primarily a book for young readers, and for girls especially. Alcott was blunt about her aims in writing about four sisters growing up in a small New England town—she once famously (and perhaps dismissively) called her work “moral pap for the young.” But to say that Little Women was written to both delight and instruct is only to say it is a book like George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871–72) or John Bunyan’s spiritual allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678, 1684), whose salubrious example is often invoked by the March parents. It is the kind of book in which readers find themselves.

Alcott knew how good a book she had written. “It reads better than I expected,” she confessed in her journal in 1868. “Not a bit sensational, but simple and true, for we really lived most of it, and if it succeeds that will be the reason of it.” This biographical dimension of the novel has undoubtedly increased our interest in the Marches, even as it has obscured their real-life antecedents (the Orchard House museum advertises itself as the home in which Alcott “set” Little Women). Tomboyish Jo was based on Alcott herself, known as Lou or Louie in the family. Like her hot-tempered counterpart, Bronson and Abba Alcott’s second daughter had a “mood pillow” and helped to support her family by writing thrillers. Unlike Jo, she would never marry. Meg was based on Alcott’s older sister Anna, who like Meg worked as a teacher but did not enjoy it. Unlike Meg, Anna went on from childhood theatricals to become an actress, performing in an amateur theater in Walpole, New Hampshire, and meeting John Pratt, the original of John Brooke, when they performed together in Concord. She married Pratt in May 1860, and had two sons, Frederick and John. Beth was based on the third Alcott sister, Lizzie. Like Beth, she was the shyest sister, nicknamed “Little Tranquility.” Lizzie loved to play the piano (she was given one by a wealthy benefactor), and left school at fifteen to stay home and help keep house. When in spring 1856 she and younger sister May both contracted scarlet fever, Lizzie never fully recovered. She died at age twenty-two. And Amy was based on May, who acknowledged as much in a letter she wrote to her friend Alfred Whitman (one of the sources for Laurie) after the book was published: “Did you recognize . . . that horrid stupid Amy as something like me even to putting a cloths pin on her nose? . . . I used to be so ambitious, & think wealth brought everything.” Like Amy, May was the pet of the family and longed to become a famous artist; a family friend paid her way to study in Boston with William Morris Hunt. She was able to study in Europe only after the success of Little Women allowed Louisa to send her. During May’s lifetime, her work was exhibited twice at the Paris Salon.

Four self-described fans of Little Women—Kate Bolick, Jenny Zhang, Carmen Maria Machado, and Jane Smiley—talk in this book about their personal connection to the novel and what it has meant to them (as children, adults, or both). More particularly, each of the writers takes in turn one of the March sisters as her subject. Kate Bolick finds parallels in the chapter about Meg attending the Moffats’ ball to her own relationship—or resonance—with clothes. Jenny Zhang, when she first read Little Women as a girl, liked Jo least of the March sisters because Jo reflected Zhang’s own quest for genius, which she feared was too unfeminine. Carmen Maria Machado writes about the real-life tragedy of Lizzie Alcott, and the horror story that can result from not being the author of your own life’s narrative. And Jane Smiley rehabilitates the reputation of Amy, whom she sees as a modern feminist role model for those of us who are, well, not like the fiery Jo. Taken together, these pieces are a testament to the ways in which Little Women, like all great books, can become so entwined in our own life narratives that we must ask ourselves whether, had we never read it, we would be fully mindful of how we have lived—or even quite fully ourselves. May these four writers inspire you to reread Little Women—

or perhaps to pick it up for the first time.

“LITTLE WOMEN was about the best book I ever read.” So began my fourth-grade book report, in 1981. Clear, if uninspired. After one-and-a-half double-spaced pages of cursive rhapsodizing in support of this daring claim, I concluded with the lazy feint of an already overburdened critic: “I would like to go on and on with this report but it would be longer than the book, so if you want to find the rest out my opinion is to read it.”

I hadn’t remembered this foray into criticism when I rediscovered it recently, at the bottom of an old wooden box in my childhood home. What I had remembered was the report’s cover art—I’d never been more proud of anything I’d made—and my mother’s irritation that I’d spent more time drawing it than I did writing about the book. Gingerly, I lifted the papers from the box and carried them to the sofa, astonished that thirty-seven years later this humble homework assignment still existed, curious to see what I’d been so worked up about.

Before I go on, I should note that though I’d loved Little Women as a child, I never thought about it as an adult. I cringe to admit how thoroughly I’d absorbed our culture’s hypocrisy toward motherhood, but for most of my life I regarded Louisa May Alcott as matronly, and therefore dull. This flagrant misconception was based entirely on the world I’d found in that book, which was so snugly familiar, both physically and emotionally, that I simply took it for granted, the way I did my own mother. Our small town on the North Shore of Massachusetts in the late 1900s—especially during a snowstorm—didn’t seem that different from Alcott’s 1800s Concord, only forty-five miles south. Even the March family’s puritanical streak ran through my own.

As I neared, my opinion changed. I was living alone in Brooklyn, working as a freelance writer, when I learned that in her thirties Alcott had lived on her own in Boston, doing the same thing. She never married or had children. She considered the social roles of “wife” and “husband” grievously prescriptive, and marriage akin to slavery, so long as women were kept economically and politically inferior to men. In February 1868, several months before she moved back home to help her parents, and started Little Women, she wrote an essay in praise of the single life, called “Happy Women.” As she noted in her diary, on Valentine’s Day no less, she had written it to celebrate “all the busy, useful, independent spinsters I know, for liberty is a better husband than love to many of us.”

Celebrating independent spinsters was exactly what I’d been working to do at the time, in my first book. Upon further digging, I learned that Alcott didn’t always feel so sanguine about her status; she was a passionate person, with strong maternal feeling, and up until her death regretted that the conventions of her era required women to sacrifice sex and motherhood if they also wanted to work. To know that she, too, grappled with the competing desires for autonomy and intimacy fascinated me, and I decided to return to Little Women to see how this ambivalent spinster had treated Meg’s marriage. Even so, I allowed several more years to pass before I actually made time for it, little knowing how much more was in store.

As when I was nine, I couldn’t put the book down. Sinking into the story, I recalled the experience of being new to reading, the capacity to completely surrender myself to fiction. I saw, too, how this particular book had marked a departure from that habit of heedless abandon, when a mental image I’d long puzzled over arose: my nine-year-old self posing on the front stoop of our house, bare feet drawn up before me, Little Women open on my knees. When my friends arrived, they would find me like this, apparently so absorbed in my reading that I wouldn’t hear their approach. So I had fantasized many times, anyway, I now realized.

Before Little Women, reading was just something I did, constantly and everywhere, at breakfast, during recess, stretched out in the backyard after school, by the fire with my parents, in bed before sleep. After reading about the March sisters’ own reading, and about how much reading meant to them, I decided that reading was a romantic act, something to be proud of—even displayed. I’d had no idea Alcott played such an active role in the shaping of my self-identity. What else had I been missing?

What luck: that old book report cover contained a clue.

With colored pencils, I’d carefully drawn a giant oval and put the March family inside it, like a miniature tableau inside a sugar Easter egg. At center in a high-backed green armchair is Jo, wearing a long lavender dress, slippered feet drawn up before her, book open on her knees, gazing straight at the viewer. Her parents stand behind the chair—authoritatively, protectively—and on the wall behind them hangs a framed portrait of Laurie, in profile. The other sisters are all in profile as well: Beth and Amy on the floor to Jo’s left, with their customary paraphernalia—one with needle and thread, the other with pad and paintbrush—and to her right, Meg in a rocking chair, embroidering, red dress bright as a Baldwin apple, long curls so lustrous they tumble out of the cameo frame. The depiction is as faithful to the novel as my report had been.

The closer I looked, however, the more I saw. Jo is the obvious protagonist of this portrait, and Meg a tantalizing lure. Even more intriguing, I’d taken creative license with the details: though Jo is famously indifferent to clothing, hers is the only dress that’s embellished with a hem of delicate pink roses, and poufed up, princess-style, with not one but two frilly lace underskirts. In comparison, Meg’s flat, unadorned frock is a nun’s habit.

I suddenly remembered how, after the first time I read Little Women, I began drawing pictures of girls in nineteenth-century fashions—hoop skirts and petticoats, aprons and cloaks, little lace-up boots with their intricate hooks and eyes. Constantly. It was a curious pastime for me. I had never been a girly-girl. The word “tomboy” fits, but imperfectly; it’s not that I wanted to be a boy, or do only boyish things, but rather that my liberal-minded parents allowed me to inhabit a gender-less space, and I looked the part. That summer, on my ninth birthday, in his consciously unsentimental “family diary,” my father described me as being “of average height, slim but not skinny. Long, light brown hair, sort of lank, which is usually messy, and tends to need washing. For some reason she resists taking baths. Horrible teeth.” School photos show I didn’t yet know to be embarrassed of my comically pronounced overbite and snaggletooth grin. Like Alcott herself, I enjoyed challenging the boys to footraces.

For Halloween that year I told my mother I wanted to be an “old-fashioned lady.” She cobbled a costume from the attic and from church sales: long black dress, long white gloves, ivory fur capelet, white fur muff, black low-heeled pumps, and a broad-brimmed velvet hat spangled with a rhinestone brooch.

I have a snapshot from that night framed on my mantel. Four children standing on a doorstep, my little brother a tiny vampire, all of them looking everywhere but at the camera, while I, the oldest, regal in my finery—the Meg of this ragtag gang—gaze steadily at the lens, my expression serene, even confident. My mouth is clamped closed to conceal my crooked teeth.

Little Women is totally ordinary, but this ordinariness is essential to its magic. Unlike other children’s masterpieces of the period—Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, the fairy tales collected by the Brothers Grimm—Alcott’s book lured readers not with fantastical adventures and talking animals, but with a realism that was radical in its forthrightness, giving voice to female adolescence. The novel articulates everyday emotions for an audience that is old enough to have experienced them, but still lacks the vocabulary necessary to express the abstractions of heightened consciousness.

At eight years old I could tell my mother that I hated the polyester red turtleneck bodysuit with snaps at the crotch she made me wear with a red plaid kilt for my school picture, but the only tool I owned to convey this opinion was my vehemence. (Also scissors, though infuriatingly, when I tried to plunge the blades into the stretchy fabric, they bounced off. The family album

shows she managed to get me into that vile garment after all.) By ten or eleven, I had absorbed enough crude rhetoric to be able to write anguished notes intended to guilt my parents into buying me the brand-name L.L.Bean snow boots I so desperately wanted. (In the end they succumbed, though to fatigue rather than guilt or a change of reasoning.)

At nine, when I encountered Little Women, I was somewhere in between. I was still very much a child, disheveled, chatty, completely immersed in imaginary worlds, and quite bossy, making other children perform in the plays I wrote, or listen to me read my stories out loud. But when the school year began, I found myself among the first in fourth grade to develop breasts. I was astonished by the intrusion, embarrassed. I didn’t mind being a girl, particularly, but in a deeply inchoate way I understood that childhood was coming to an end and life held in store many more ordeals. Newly self-conscious, I noticed for the first time that my best friends, a pair of fraternal twins with limpid eyes, sweet bow lips, and thick waves tamed with darling barrettes, were what adults called “such pretty girls,” and that I wasn’t. Once again I lacked the language to express any of this.

It wasn’t the first time fiction had presented me with a mirror. I had seen much of myself in Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby, and Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne Shirley, though in that case too much—buck-toothed, scrawny, freckled, talkative, blown every which way by emotional gusts. What was the point in reading about myself? I gave up after the first book in the series. At first, Little Women seemed the same, offering me Jo, another reflection. A tomboy who writes stories. So what, didn’t we all? She even resembled me: “big hands and feet, a fly-away look to her clothes, and the uncomfortable appearance of a girl who was rapidly shooting up into a woman, and didn’t like it.” Begrudgingly I soldiered on, vaguely annoyed to be saddled with yet another doppelgänger, and increasingly suspicious of Jo’s insistence that looks don’t matter, when in real life I was beginning to sense that the opposite was true. One afternoon during recess, my teacher gently called me aside. Would I like her to raise the issue of braces with my parents? Until that moment, I hadn’t realized that the jokes the other kids made about my teeth weren’t meant to be funny, but mean.

March Sisters

March Sisters